Timacum Minus

Protected cultural monument of great significance, listed as AN 37 with the Republic Institute for the protection of monuments of cultural heritage.

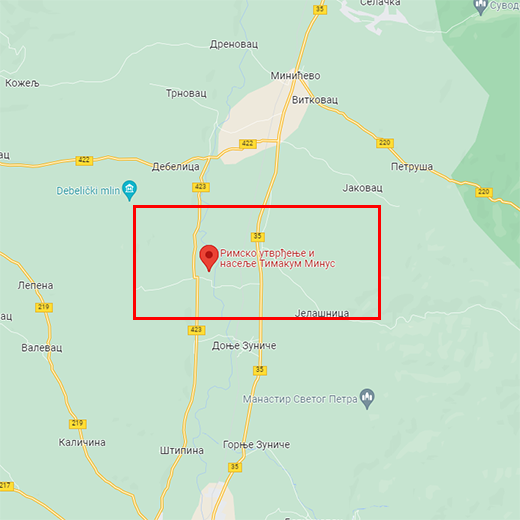

Timacum MinusZaječar administrative district

Where is it

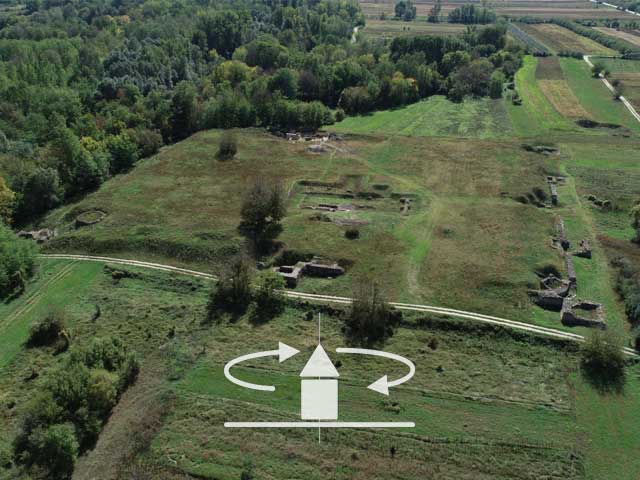

The remains of the ancient fortification Timacum Minus are located in the today’s village Ravna, northeast from the village, on the left bank of Beli Timok, en route of Roman road from Nis to Ratijarija in Bulgaria (Naissus-Ratiarija). They are about 9 km north of Knjaževac, on the road towards Zaječar.

Research

Archaeological research in Ravna village began in late 19th and early 20th century by Anton von Premerstein from Austrian Archaeological institute and Nikola Vulić, professor from the University of Belgrade. Systematic research organized by Archaeological institute from Belgrade and Homeland museum of Knjaževac begun in 1975. Fortress ramparts and parts of civilian settlement with thermal baths and necropolis were discovered.

Necropolis on the Slog hill was researched between 1994 and 1996, and continued in 2013 and 2014.

In 2010 Archaeological institute from Belgrade, Homeland museum Knjaževac and Roman-German commission from German Archaeological institute from Frankfurt performed a geophysical recording of the area, in order to establish the layout of archaeological remains, especially the walls, in the field.

The result of this research is the knowledge that in the location of the fortification there is a continuity of settlement from prehistory to the middle ages. This is the crossroads of the roads from north to the south and from east to the west. Ore deposits in Stara mountain caused the occupation of the residents and the entire economy. Epigraphic inscriptions confirmed that Timacum Minus used to be the center of a wider region.

Dating

In written sources, the fortification Timacum Minus is mentioned as early as 78, as the seat of the Roman army cohort I Tharacum -Siria, after the transfer of the unit to Moesia. A significant restoration came about in III-IV century when more towers were built and older tombstones were used for building. The last restoration happened in VI century, at the time of Justinian. The fortification represented an important link within the inner limes, fortified for the protection from barbaric intrusions.

Researched objects

Building in the central part of the fortification (horrreum)In the central part of the fortification, a rectangular building was discovered, whose southern façade faces the north side of the main street which connects east and west (decumanus). It was built with the combination of rows of brick and stone tied with quicklime mortar – a technique known as mixtum. The building had an upper floor supported by columns that also fortified the walls of the ground floor. Although it was originally believed to be a granary, it is possible that the building was in fact a principia, the seat of administrative-military authority of the castrum Timacum Minus in the IV century.

Circular archaeo-metallurgical object

In the northeast corner of the fortification, a circular edifice was discovered, with a pool in the middle, 6 m in diameter. It was built with stone and mortar, with waterproof mortar on the floor. The analyses of samples from the object point out that ore flotation was performed here as well as separation of silver and gold.

Southern gate (porta praetoria)

The southern gate of the fortification is largely preserved. It has a special building technique, as it was partly built with large stone blocks of sandstone, in drywall technique (without binding material), which points out to the work of local craftsmen. The gate was protected by rectangular towers.

Thermal baths (Terme I)

Thermal baths were discovered outside the walls of the fortification, to the northeast, next to the bank of Beli Timok. On the east side of the building there is changing room - apodyterium, in the continuation is the tepidarium, room with lukewarm water. On the other side, there are two rooms with hot water– caldaria, connected to the firebox – praefurnium. On the south side there is a pool with cold water– frigidarium. Thermal baths were built with crushed stone and pebbles and were used while the fortification was in function.

Belief and rituals

West from the fortification, on the Slog locality, a part of late antique necropolis was discovered and researched. In the late III and early IV century the deceased were buried both by cremation and burial.

In the layer above the antique one, the remains of a Slavic necropolis were discovered, from IX-X century, judging by the way of burial.

The research of necropoli indicated the beliefs of the peoples, as well as the changes in social and economic status of the community.

Apart from the Roman tradition, some graves contain barbaric rituals, such as combs made of deer antlers.

The first half of the V century, judging by the burial practices, indicates that the inhabitants have adopted Christianity. The deceased are buried mostly without accompanying gifts, in straight positions. That also indicates that they became poorer.

The youngest phase, medieval necropolis IX-X century is typically Slavic. The deceased were placed on their backs, heads facing the West. Some graves contained jewelry or personal items. Ritual breaking of vessels in order to drive away evil is also noticeable. Sometimes they would put an egg inside the grave, as the symbol of renewal of life.

Within the cult of the dead, there was the custom of funeral feast – the layer above the grave contained pig and chicken bones. The traces of burning pyres near the graves were discovered in the Slog necropolis. It was believed that the fire purifies and destroys evil.

As the necropolis has always been a special cult place between the world of the living and the world of the dead, it is not unusual that the funeral customs had as their aim to ease the transition to the other world, with a dignified farewell.

Јулка Кузмановић Цветковићархеолошкиња